Drew McCoy, aka the Genetically Modified Skeptic (YouTube), talks about the occult, skepticism, gnosticism, and more with Dr. Justin Sledge of Esoterica (YouTube).

Andrew McCoy, better known online as Genetically Modified Skeptic, is an American atheist YouTuber who makes videos about atheism, responses to religious videos, and has also criticised alternative medicine.

Esoterica is an ongoing project of Dr. Justin Sledge where he produces video content on Youtube to explore topics in Western esotericism such as magic, mysticism, alchemy, kabbalah, hermetic philosophy, theosophy, and more.

How to be an atheist

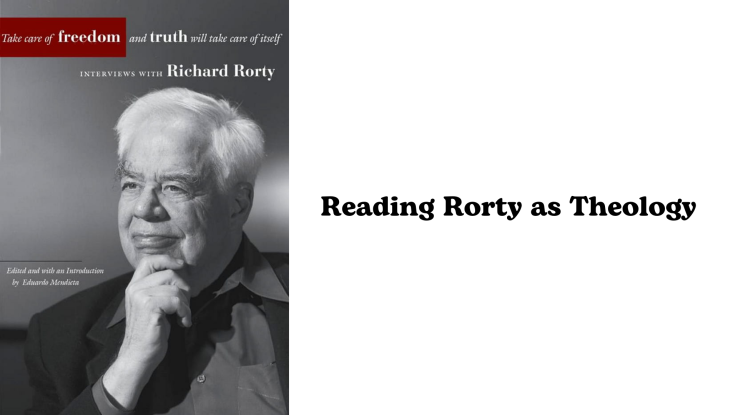

John Gray

Contemporary atheism is a flight from a godless world. Life without any power that can secure order or some kind of ultimate justice is a frightening and for many an intolerable prospect. In the absence of such a power, human events could be finally chaotic, and no story could be told that satisfied the need for meaning. Struggling to escape this vision, atheists have looked for surrogates of the God they have cast aside. The progress of humanity has replaced belief in divine providence. But this faith in humanity makes sense only if it continues ways of thinking that have been inherited from monotheism. The idea that the human species realizes common goals throughout history is a secular avatar of a religious idea of redemption.

Atheism has not always been like this. Along with many who have searched for a surrogate Deity to fill the hole left by the God that has departed, there have been some who stepped out of monotheism altogether and in doing so found freedom and fulfilment. Not looking for cosmic meaning, they were content with the world as they found it.

By no means all atheists have wanted to convert others to their view of things. Some have been friendly to traditional faiths, preferring the worship of a God they think fictitious to a religion of humanity. Most atheists today are liberals, who believe the species is slowly making its way towards a better world; but modern liberalism is a late flower of Jewish and Christian religion, and in the past most atheists have not been liberals. Some atheists have gloried in the majesty of the cosmos. Others have delighted in the small worlds human beings make for themselves.

While atheists may call themselves freethinkers, for many today atheism is a closed system of thought. That may be its chief attraction. When you explore older atheisms, you will find that some of your firmest convictions – secular or religious – are highly questionable. If this prospect disturbs you, what you are looking for may be freedom from thinking. But if you are ready to leave behind the needs and hopes that many atheists have carried over from monotheism, you may find that a burden has been lifted from you. Some older atheisms are oppressive and claustrophobic, like much of atheism at the present time. Others can be refreshing and liberating for anyone who wants a new perspective on the world. Paradoxically, some of the most radical forms of atheism may in the end be not so different from some mystical varieties of religion.

Defining atheism is like trying to capture the diversity of religions in a formula. Following the poet, critic and impassioned atheist William Empson, I will suggest it is an essential part of terms like ‘religion’ and ‘atheism’ that they can have multiple meanings. Neither religion nor atheism has anything like an essence. Borrowing an analogy from the Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, they are more like extended families, which display recognizable similarities without having any single feature in common. This view inspired the American pragmatist William James to write The Varieties of Religious Experience, the best book ever written on religion by a philosopher and one that Wittgenstein much admired.

A provisional definition of atheism might still be useful, if only to indicate the drift of the book that follows. So I suggest that an atheist is anyone with no use for the idea of a divine mind that has fashioned the world. In this sense atheism does not amount to very much. It is simply the absence of the idea of a creator-god.

There is precedent for thinking of atheism in these terms. In the ancient European world atheism meant the refusal to participate in traditional practices honouring the gods of the polytheistic pantheon. Christians were described as ‘atheists’ (in Greek atheos, meaning ‘without gods’) because they worshipped only one god. Then as now, atheism and monotheism were sides of the same coin.

If you think of atheism in this way you will see that it is not the same as the rejection of religion. For most human beings religion has always consisted of practices more than beliefs. When Christians in the Roman Empire were required to follow the Roman religion (religio in Latin), this meant observing Roman ceremonies. These included acts of worship to pagan gods, but nothing was demanded in terms of belief. The word ‘pagan’ (pagani) is a Christian invention applied in the early fourth century to those who followed these practices.1 ‘Paganism’ was not a creed – the people described as pagans had no concept of heresy, for one thing – but a jumble of observances.

A provisional definition of religion may also be useful. Many of the practices that are recognized as religious express a need to make sense of the human passage through the world. ‘Birth, and copulation, and death’ may be all there is in the end. As Sweeney says in T. S. Eliot’s Fragment of an Agon – ‘That’s all the facts when you come to brass tacks.’ But human beings have been reluctant to accept this, and struggle to bestow some more-than-human significance on their lives. Tribal animists and practitioners of world faiths, devotees of flying-saucer cults and the armies of zealots that have killed and died for modern secular faiths attest to this need for meaning. With its reverent invocation of the progress of the species, the evangelical unbelief of recent times obeys the same impulse. Religion is an attempt to find meaning in events, not a theory that tries to explain the universe.

Rather than atheism being a worldview that recurs throughout history, there have been many atheisms with conflicting views of the world. In ancient Greece and Rome, India and China there were schools of thought that, without denying that gods existed, were convinced they were not concerned with humans. Some of these schools developed early versions of the philosophy which holds that everything in the world is composed of matter. Others held back from speculating about the nature of things. The Roman poet Lucretius thought the universe was composed of ‘atoms and the void’, whereas the Chinese mystic Chuang Tzu followed the (possibly mythical) Taoist sage Lao Tzu in thinking the world had a way of working that could not be grasped by human reason. Since their view of things did not contain a divine mind that created the universe, both were atheists. But neither of them fussed about ‘the existence of God’, since they had no conception of a creator-god to question or reject.

Religion is universal, whereas monotheism is a local cult. Many ‘primitive’ cultures contain elaborate creation myths – stories of how the world came into being. Some tell of it emerging from a primordial chaos, others of it springing from a cosmic egg, still others of it arising from the dismembered parts of a dead god. But few of these stories feature a god that fashioned the universe. There may be gods or spirits, but they are not supernatural. In animism, the original religion of all humankind, the natural world is thick with spirits.

Just as not all religions contain the idea of a creator-god, there have been many without any idea of an immortal soul. In some religions – such as those that produced Norse mythology – the gods themselves are mortal. Greek polytheists expected an afterlife, but believed it would be populated by the shades of people who had once existed, not these people in a posthumous form. Biblical Judaism conceived of an underworld (Sheol) in much the same way. Jesus promised his disciples salvation from death, but through the resurrection of their fleshly bodies, divinely perfected. There have been atheists who believed human personality continues after bodily death. In Victorian and Edwardian times, some psychical researchers thought an afterlife meant passing into another part of the natural world.

If there are many different religions, there are also many different atheisms. Twenty-first-century atheism is nearly always a type of materialism. But that is only one of many views of the world that atheists have held. Some atheists – such as the nineteenth-century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer – have thought that matter is an illusion and reality spiritual. There is no such thing as ‘the atheist worldview’. Atheism simply excludes the idea that the world is the work of a creator-god, which is not found in most religions.

John Gray, Seven Types of Atheism. London: Allen Lane, 2018.

RELATED CONTENT: